The Knee Joint

The knee joint can be thought of as a hinge joint with the primary motion of straightening and bending. In reality, it is more complex than a simple hinge, as the surfaces actually glide and roll upon one another. It is composed of the end of the thigh bone (femur), the top of the leg bone (tibia), and the kneecap (patella).

The ends of the bone are covered with a smooth, glistening layer called articular cartilage. The articular cartilage is what allows the bones to glide smoothly with less resistance than ice sliding on ice. The articular cartilage can be seen on x-ray as the space in between the bones.

The knee can be thought of as having 3 compartments – the medial, the lateral, and the patellofemoral. In addition, there are 2 special cartilages within the knee joint called the lateral and medial meniscus, which act as shock absorbers within the knee joint. There are also 2 ligaments within the knee, called the anterior cruciate ligament and the posterior cruciate ligament, which contribute to knee stability.

|

|

Arthritis of the Knee

Arthritis of the knee is a condition in which there is loss of the articular cartilage of the femur, tibia, or patella. This can be seen on x-ray as a loss of the space between the two ends of bone.

Because of the loss of the gliding surfaces of the bone, people with arthritis may feel as though their knee is stiff and their motion is limited. Sometimes people actually feel a catching or clicking within the knee. Generally, loading the knee joint with activities such as walking long distances, standing for long periods of time, or climbing stairs makes arthritis pain worse. When the arthritis has gotten to be severe, the pain may occur even when sitting or lying down. The pain is usually felt in the inside part of the knee, but also may be felt in the front or back of the knee. As the cartilage is worn away preferentially on one side of the knee joint, people may find their knee will become more knock-kneed or bow-legged.

Arthritis of the knee usually occurs in people as they enter their 60′s-70′s, but this is variable depending upon factors such as weight, activity level, and knee anatomy. Arthritis may be caused by a variety of factors, including simple wear and tear, inflammatory disorders such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, infections, and post-traumatic. People who have had prior injury to their knee, damaging the meniscus or cruciate ligament may also develop arthritis. The end result of all these processes is a loss of the cartilage of the knee joint, leading to bone rubbing against bone.

Treatment of Knee Arthritis

Depending upon the severity of arthritis and the patient’s age, knee arthritis may be managed in a number of different ways. Treatment may consist of operative or non-operative methods, or a combination of both.

Non-operative

The first line of treatment of knee arthritis includes activity modification, anti-inflammatory medication, and weight loss. Giving up activities that make the pain worse may make this condition bearable for some people. Anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen, naprosyn and newer Cox-2 inhibitors help alleviate the inflammation that may be contributing to the pain.

Physical therapy to strengthen the muscles around the knee may help absorb some of the shock imparted to the joint. This is particularly true for knee-cap (patello-femoral) arthritis. Special kinds of braces, designed to place transfer load to a part of the knee that is less arthritic may also help relieve the pain. Injections of medication inside the knee joint may also help alleviate the pain temporarily.

Furthermore, walking with a cane in the hand on the opposite side as the painful knee may help distribute some of the load, reducing the pain. Finally, weight loss helps decrease the force that goes across the knee joint.

A combination of these non-operative measures may help ease the pain and disability caused by knee arthritis.

Operative

If the non-operative methods have failed to make your condition bearable, surgery may be the best option to treat knee arthritis. The exact type of surgery depends upon your age, anatomy, and underlying condition. Some examples of surgical options to treat arthritis include an osteotomy, which consists of cutting the bone to realign the joint; and knee replacement surgery.

An osteotomy is a good alternative if the patient is young and the arthritis is limited to a one area of the knee joint. It allows the surgeon to realign the knee to unload the arthritic area and place weightbearing on relatively uninvolved portions of the knee joint. For example, a patient who has begun to become more bow-legged might be realigned to be more knock-kneed in order to redistribute the load across the joint. The advantage of this type of surgery is that the patient’s own knee joint is retained and could potentially provide many years of pain relief without the disadvantages of a prosthetic knee. The disadvantages include a longer rehabilitation course and the possibility that arthritis could develop in the newly aligned knee.

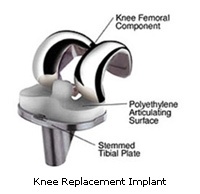

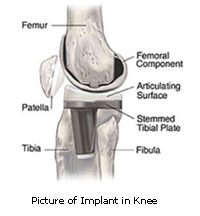

Knee replacement surgery involves cutting away the arthritic bone and inserting a prosthetic joint. All of the arthritic surfaces are replaced, including the femur, tibia, and patella. The arthritic surfaces are removed, and the ends of the bone are replaced with the prosthesis, like capping a tooth. The prosthetic component is generally made of metal and plastic surfaces which are designed to glide smoothly against one another.

|

|